The last Lenin.

There used to be a statue of Lenin in Osh. Twenty-three metres tall, that specimen of Vladimir Ilic Ulyanov towered over Kyrgyzstan’s second city since 1975.

I stumbled into it, almost by accident. It wasn’t June yet but, already, the heat hung over the Ferghana valley like a sarcophagus. Mattia and I were chasing shadows along Leninskiy prospekt when we saw it: one hand holding the lapel of that famous trench coat, the other extended outwards. “It looks as if he’s telling where to park your car” commented Mattia.

That Lenin, however, is no more. This June, eight years since our visit, Osh city council removed it at the crack of dawn, with little notice or fanfare. Leninskiy Prospekt too fell by the wayside, renamed after a local politician. Another statue of Lenin was to be removed in Kyrgyzstan, this time in Jalal-abad, shortly after.

As somebody who had the good fortune never to have known life under Communism, I always felt an odd fascination for monuments depicting this balding man in a coat and suit. Round where I’m from, statues in squares might depict royals on horseback or saints. What was it like to be living here instead? What did those who erected to statue think? What did people make of them.

The current feeling, I guess, is unambiguous. From Armenia to Uzbekistan I strolled in the shadows of plinths that once held Lenin aloft but went on to host a veritable pantheon of alternatives. Sure, some endured – I saw them in Hanoi, Cholpon Ata and Murghab – but they felt like exceptions, holdouts like those Japanese soldiers who were never told of the armistice in 1945.

There is one statue, though. One Lenin depiction, bronze frown and all, that doesn’t seem to be in a hurry to be moved away. And it’s not where you’d expect it to be.

Eighty kilometres west of Bologna, within commuting distance from the factories where Ferrari, Ducati, Lamborghini and Pagani are made, is Cavriago. Nine thousand souls on Reggio Emilia’s doorstep, as a song goes, and smack-bang at its centre is Piazza Lenin. And in that square, is a bust of Lenin.

Now, this will require some explaining. You might be excused for finding Italians to be right-leaning, and you wouldn’t be wrong; but there are a couple of areas, popularly known as Regioni Rosse, where the political left has a long and storied history. Emilia-Romagna is one of them and Cavriago is one of its epicentres. Socialists, there, were name-checked by Lenin himself in a speech on the eve of the Bolshevik revolution. From the 1950s to the fall of the Berlin wall the PCI – the Italian Communist party – always got at least 65% of votes, and one person in five were literally card-carrying Communists. Even in the last mayoral elections, in 2024, the left-leaning candidates got 78% of preferences.

A couple of years ago, accompanied by a local friend as a guide, I paid a visit to Cavriago. It was a typically Northern summer day: the sun was a hammer and our heads its anvils. Humidity hovered around Vietnamese levels. After a climatically inappropriate lunch of cheese, Parma ham and fried gnocchi we headed over to Cavriago, parked in Piazza Lenin and there it was. The man itself.

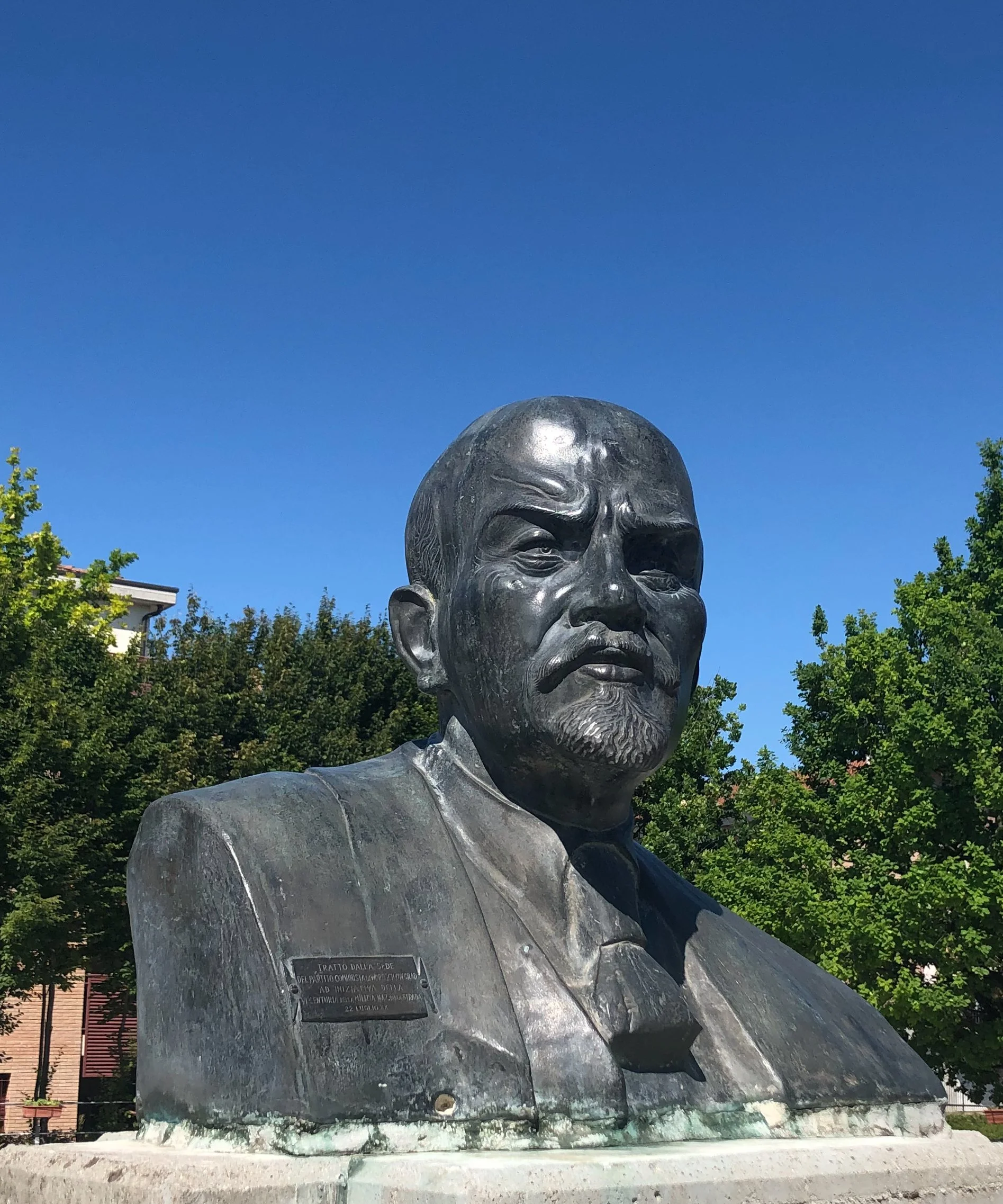

The bust was small, dark bronze sitting atop a concrete pillar. Lenin was depicted with his characteristic frown, one shoulder slumped and another – cut before it could turn into a waving arm – raised. The lapel of his jacket was just accented, and he wore a button-down shirt with a tie puffed up by an invisible stick pin.

A gaggle of local teenagers sat in the shadow of the piazza, ignoring us and the statue. I suppose they were used to it, much as they must’ve been used to the odd tourist coming around. We were about to leave when four more visitors appeared, emerging out of a camper van with French numberplates. “We heard about this statue”, they told us in good Italian, “But we didn’t believe it. Lenin here?” they asked, putting the accent on the first vowel. Lénine.

This was my local friend’s chance to shine. Now rewarded with an international audience, she told us the story of this statue. And, as it always happens in Italy, it was more complex, convoluted and haphazard that a cinematographer would dare envisaging.

This bust started life in Luhansk – today occupied by Putin’s regime - when, caught by Socialist fervour, workers at the local locomotive factory decided to melt down a reactionary church bell to cast a bust of Lenin. The year was 1922, Lenin was still very much alive, and the bust was placed outside the factory building. Then, when Lenin ascended to whatever passes for Socialist heaven, the bust moved locations a few times before finding its lasting location outside the Luhansk branch of the Soviet Communist party.

Or so everyone thought.

When Hitler launched Operation Barbarossa his pal Mussolini decided to contribute to the adventure with a quarter of a million men, thinking that it couldn’t possibly go bad (spoiler alert: a third of those men wouldn’t make it back). As they advanced through Ukraine, the Italians occupied Luhansk and, upon seeing that very Lenin bust, they decided to nick it. The bust was sent to Rome as war loot.

Then things got complicated. Italy was invaded by the Allies, surrendered, and was divided in two. No one is quite sure of what happened to the bust in those convulsed days (there might, or might not, have been a rescue by Tuscan partisans, for instance), but eventually the bust – now scarred by a bullet – was returned by the new Italian republic to the Soviet ambassador.

That would be the end of that, one would assume, were it not for the fact that, in 1970, Cavriago decided to celebrate Lenin’s 100th birthday by twinning with a Soviet city. Bender, in the Moldovan SSR, was selected and the Soviets sent a bust of Lenin to Emilia-Romagna to cement the deal.

Dutifully impressed, we gave Lenin one last glance and left on our separate ways. But, once home, I found out that this wasn’t the entire story. Though Cavriago was always due a Lenin, it wasn’t going to be the old Luhansk one.

This latest plot twist has two protagonists. One, Piero Cadoppi, worked for the local dairy cooperative and had a van. The other, Rodolfo Curti, was a PCI cadre; he spoke Russian and had even studied in Moscow in the 1960s. It all began when, one day, Piero got in his van and drove to Rome to pick up the bust of Lenin that the Soviet people had gifted to their Italian comrades.

The trip was a bust. Piero drove to via Gaeta, at the Soviet embassy, only to find that the statue of Lenin that had arrived from the USSR was wrapped in a huge crate, far bigger than Piero’s van. Like Amity Island’s Chief Brody, he needed a bigger van. He also needed somebody who could speak at least some Russian and so it was that, on his second trip, Rodolfo was sitting with him in the cab of a larger truck.

Back in Rome the two friends from Cavriago asked if they could peer into the sarcophagus that hid the statue of Lenin away from prying eyes. What appeared was a scagliola behemoth, and not only that; it was “devoid of any personality, looking like any other of the thousands such statues that peppered the Soviet Union”, said Rodolfo, who’d seen plenty of Lenins in his time in the USSR.

Piero and Rodolfo were in a right pickle. That statue was gargantuan and ugly, no one would like it in Cavriago. Sure, they were Communists; but they were Italians too, and thus valued beauty. The scagliola monstrosity just wouldn’t fly. But then, hidden between some plants in the lush courtyard of the Soviet embassy, they found their solution.

The Luhansk Lenin.

There was just the little issue of convincing the Soviets to let them have a statue other than the one they’d come for. A scagliola-for-bronze trade, if you will. The staff of the embassy was, predictably, puzzled. “What are we going to do with this one, then?” they asked while pointing at the chalk statue. Rodolfo was playing hardball: “Do what you want with it; we’re taking this one”. The Soviets played for time, but Rodolfo was, once again, having none of it. “We don’t have any time, the twinning is very close, we can’t come down to Rome again”.

Eventually, the Soviets relented. The Cavriago duo could have the Luhansk bust, and they could come and pick it up later. But Piero was already backing up the van into the embassy, much to the surprise of the diplomats, and then off they were, home bound, a bronze statue in the back.

There is nothing, in my opinion, to object to the disappearance of Lenin statues in the former Eastern bloc; they were reminders of oppression and, even if they weren’t, it’s a local issue and I shan’t meddle. But I hope that the Lenin in Cavriago will stay on. As a symbol of a past of struggle and, if nothing else, for the story that it carries.