The fourth stage of culture shock.

I once lied on a university assignment.

The task was to write about culture shock and, in my paper, I described the experience of my first real overseas trip to Japan. The paper was well received but, as I said earlier, there was a lie within it. You see, the classic model of culture shock is predicated on the person going through a four-stage rollercoaster: honeymoon, frustration, adaptation and acceptance. My paper detailed my experience through the first three steps but, truth be told, the last one was an invention. The reality is that, by the time I flew back to Europe, I’d scarcely adapted – to say nothing of accepted – the reality of being a foreigner in Japan.

I can still recall the feeling of sheer excitement in my first days in Tokyo. The Asakusa hostel had a terrace that looked towards Ueno and the skyscrapers of Nihonbashi. Trains flowed on overhead tracks and music blared from giant screens at traffic lights. Hairdos defied gravity, cars exceeded those in Vin Diesel’s films. This was city of Blade Runner twinned with Coruscant and there I was, in the middle of it, mouth agape.

Frustration came gradually at first, and then all of a sudden. Unable to communicate, illiterate whenever a Latin letters translation wasn’t provided, I felt at best ignored and at worst ostracized. Street promoters wouldn’t hand me leaflets, it was impossible to struck even a casual conversation, and the few interactions to be made were with fellow Western backpackers. Then, and in a subsequent work visit, I stumbled into more than one establishment with a sign, scribbled in pencil, that said “No foreigners”.

Time passed, including a pandemic-induced shutdown that lasted almost three years. But as the shutters came back up, we planned a return.

For three weeks we roamed the country. From the northern reaches of Hokkaido to the tropical Ryukyus and a bit inbetween. We flew, bussed, cycled and drove. We took trains, coaches and our own feet to move across towns, villages and lonesome country roads and, in so doing, something that felt like a different Japan began to unfurl before our eyes.

One of the most recurring descriptions of Kushiro is that Hokkaido’s charms lie elsewhere. True to form, in the fading light of the day this industrial city managed to appear both empty and gloomy, its wide boulevards devoid of pedestrians or even cars.

Yet, a tiny knot of street beckoned. Tiptoeing towards the waterfront, where the sea lurked behind concrete revetments, Kushiro’s restaurant district had just opened for the night, and we’d worked quite an appetite during our drive north from Sapporo.

The establishment of our choice was, at its core, a long room with scant light and dark panelling. The kitchen was open plan, with a line of stools ringside and, lining the opposite wall, a row of booths where you pressed the sort of call bell on sale in hardware stores to catch the attention of one of the waiters. The menu was only in Japanese and Google Translate had seemingly taken the day off.

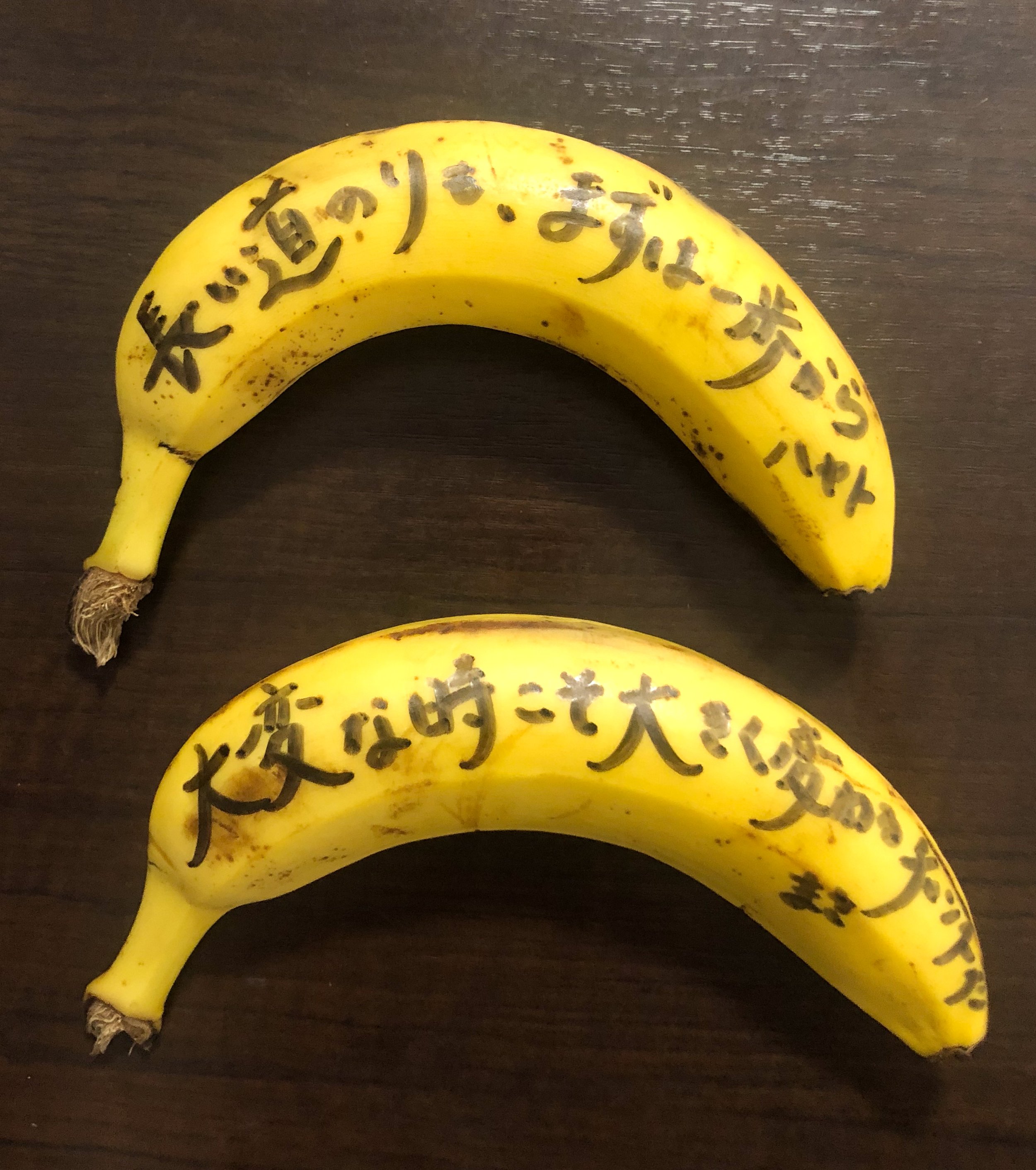

We ordered based on the few photos found in the menu, snippets of general knowledge we could remember and, well, the luck of the draw. Beers flowed liberally and so did our laughs. When the time came to leave everyone, including the surly patriarch perched behind the cash registry and some of the remaining customers, saluted. One of the waiters escorted us to the door, handed us a small bundle before bowing and waving as we walked back to the hotel. There, we saw that it contained two bananas on which two messages had been written with a soft-tip pen.

長い道のりも、まずは一歩から。大変な時こそ大きく変わるチャンスだ。

Even a long journey starts with a single step. Difficult times are an opportunity to make big changes.

The bus should’ve arrived at Gokayama twenty minutes ago. Everywhere else, this would’ve been just a minor annoyance; in Japan, such a delay was surefire promise of some sort of gargantuan catastrophe. Sure, this wasn’t a bad place to wait – the weather was nice, the bakery had just opened and there were a vending machine and an immaculate public toilet to care of the two other basic needs – but the bus to Takaoka were infrequent and the next one would only be in the afternoon.

Around us, it was just another morning in the Japanese Alps. The similarities between this place and the low-altitude villages I used to frequent as a child were staggering. The same trees, the same V-shaped valleys dug by torrents and even the same village vibe. Here was the dusty supermarket; there was the hardware store with the chainsaw logo stickers peeling in the sun. Further down there was the hulking mass of the local agri-cooperative. Had it not be for the cars, the pagoda roofs and the signs in hiragana, this could’ve passed for Pont-Saint-Martin or Fobello.

Sure, what lay halfway upslope from there – the gassho-zukuri village of Ainokura, or the temples in the forest – had nothing in common with the Italian Alps; but that was yesterday’s discovery and, today, we were without a ride to get us back home in Kanazawa. Thirty minutes went by, then forty. It was now almost 10 in the morning and the next bus, according to the schedule stabled on the post, wouldn’t arrive until 2 in the afternoon.

We were considering hitch-hiking when a tiny Mazda stopped. Inside was the owner of the guesthouse we’d stayed at, a genial man in his 60s. he spoke limited English and, with our Japanese ending at “Konnichiwa”, we had to rely on Google Translate. Using his phone he asked us if we’d missed the bus. It hadn’t come, we Googled back.

Not to worry, he replied, smiling. He could take us to Johana, some twenty kilometres downhill. And so it was that an almost complete stranger picked us up and delivered us to a train station lifted straight out of a manga, where an equally Miyazaki-esque train awaited to take us on a journey past small hamlets, rice paddies and ladies wearing wide hats while they rode Dutch bikes.

When we tried to offer our saviour something in return for his detour he smiled and, through Google Translated, declined our gesture. “People should always help people”.

There’s a pub in Miyako city. True to its tropical location, it is the quintessential surfer hangout and, in the opinion of a friend who practices the double art of riding waves and be cool at all times, Island Brewing’s got the looks pretty much dialled in.

The beers on tap might have London prices and the largest serving is still well short of being a proper pint, but these are minor shortfalls for a place that puts Fontella Bass, Martha & The Vandellas and Bob Dylan on the turntable. Needless to say, it became a go-to place during our short stay in Miyakojima and, early after sundown, we’d find our way to a couple of stools by the bar.

This was the sort of place where one could feel like walking barefoot or strike a random conversation with fellow drinkers or with the staff. Of the latter, the bartenders alternated between a man in his 40s who could’ve passed for a physicist turned surfer and a young woman with a penchant for the bucket hats made popular by the 1990s Manchester scene.

Our last evening, perhaps sensing the impending end, a plate of tacos arrived announced at the bar. As we made to leave the young lady who’d been giving us tips on beers looked at Better Half and, with a shy smile, told her “You’re beautiful”.

What happened to Japan? I struggled to recognise the country where I had an almighty hard time making connections in 2008 with this kind, open and hospitable archipelago we visited in 2023. Perhaps fifteen years had made its people less shy and afraid. Perhaps it’s due to globalisation.

Or perhaps nothing’s changed; it’s been there all along, and what changed is not them, not this place, but me. Perhaps I’ve become less brash, more mature, capable of – as they say – walking a mile in someone else’s shoes.

Maybe this is the final stage of that culture shock process that started all those years ago.